-

-

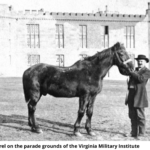

General Stonewall Jackson

On the second day of the battle of Chancellorsville, May 2, 1863, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia experienced its greatest tactical success and, at the same time, suffered its most grievous casualty. Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson led his Confederate 2nd Corps on a devastating attack against the vulnerable right flank of the Union Army of the Potomac. The southern assault overwhelmed the unsuspecting Union XI Corps and drove it nearly three miles before the Federals managed to form a defensive position in the densely wooded region south of the Rapidan River know as the “Wilderness.” A little after 9 p.m. Gen. Jackson, anxious to continue the attack, rode forward of the still-forming main Confederate line with members of his staff to assess the situation. In the darkness southern infantrymen mistook them for Union cavalry and fired a volley into the mounted men. Three bullets struck Jackson while others in his party were killed or wounded.

Among those riding with the general was Capt. Richard Eggleston Wilbourn, Jackson’s signal officer. In the chaos that followed, Wilbourn and several others tended to the general and helped get him to an ambulance that carried him to a field hospital where Jackson’s left arm was amputated. The next day he was taken to a safe place south of Fredericksburg to recover. But a week later, on May 10, Jackson died from pneumonia. Before the general died, Capt. Wilbourn wrote an eight-page letter to Col. Charles J. Faulkner, assistant adjutant general on Jackson’s staff, describing in detail the events surrounding the general’s wounding. That letter is preserved in the society’s manuscripts collection. A complete transcription of Wilbourn’s letter appears below.

Transcription:

HQ 2nd Army Corps

May 1863

Col. C. J. Faulkner,

A.A. Gen.

Sir,

At your request I will endeavor to give you a correct account of the manner in which Gen. [Thomas J.] Jackson was wounded. Gen. J. attacked the enemy in the rear near the Wilderness Church on the evening of the 2nd of May and drove the enemy before him till about 9 o’clock p.m. when the firing ceased. The road on which we were advancing ran nearly due east & west & our line extended across this road & at right angles to it, our front being towards Chancellorsville or facing east. The gallant [Brig. Gen. Robert E.] Rodes with his veterans drove the enemy at the rate of nearly two miles per hour, and cheer after cheer rent the air as our victorious columns drove the enemy from his chosen position. I have never seen Gen. J. seem so well pleased with his success as that evening—he was in unusually fine sprits and every time he heard the cheering of our men which is ever the signal of victory—he raised his right hand a few seconds as if in acknowledgement of the blessing and to return thanks to God for the victory. About 9 o’clock the firing ceased and all seemed quiet and Gen. J. ordered Maj. Gen. A. P. Hill to the front to relieve Gen. Rodes whose command had been engaged all the evening and who was consequently ordered back to the rear to rest his troops. Gen. J. now rode to the front and meeting Gen. R. said to him “Gen. I congratulate you and your command for your gallant conduct and I shall take pleasure in giving you a good name in my report,” and rode on to the front passing Gen. Hill, who was in front getting his command in position & fortifying his line—Gen. J. ordered Capt. [James K.] Boswell, his Chief Engineer to report to Gen. Hill for orders and sent Capt. [James P.] Smith, his aide-de-camp off with

[page 2]

orders. Maj. [Alexander S.] Pendleton, A. A. Gen. had previously been sent off with orders. I had just returned from carrying an order and had just reported that his order had been delivered, when he replied as is his custom “very good.” So there was no one left with Gen. J at this time, but myself and Messrs. Wm. E. Cunliffe & W. T. Wynn of the Signal Corps, and Capt. [William F.] Randolph in charge of the few couriers present. Gen. J with this escort was now at about fifty or sixty yards more or less distance in advance of Gen. Hill who was in advance of his troops. Gen. [James H.] Lane’s Brigade extended across the road just in the rear of Gen. Hill, and commended firing at us from the right for some cause I suppose taking us for the enemy and the firing extended unexpectedly along his whole line. When the firing commenced all our horses had been frightened and started off—some moving into the enemy’s lines. At the first fire some of the horses were shot from under their riders and several persons killed or wounded. Mr. Cunliffe of the Signal Corps fell in a few feet of Gen. J., mortally wounded. Gen. J.’s horse dashed off in the opposite direction, that is to the left, at the first firing, as did all of the escort who escaped this fire & who could control their horses. I was at Gen. J.’s left side & kept there. When we had gotten about fifteen or twenty paces to the left of the road, we came up in a few yards of the troops of this same Brigade on the left of the road and received their fire, as the fire had by that time extended to the extreme left of the Brigade and it was by this last fire that Gen. J. was struck in three places, viz, in the left arm half way between the elbow & shoulder, in the left wrist, and in the palm of the right hand. The troops who fired at us did not appear to be more than thirty yards off, as I could see them though it was after 9 o’clock P.M. He held his reins in his left hand which immediately dropped by his side and his horse perfectly frantic dashed back into the road, passing under the limb of a tree which took off his cap, and ran down the road towards the enemy. I followed, losing my cap at the same bush—but before I could catch his horse & when about fifty yards from where he was wounded, he succeeded in getting

[page 3]

his reins in his right hand—also disabled—and turned his head towards our lines and he then ran up the road. We were now so far in advance of our troops as to be out of their range. Just as his horse got within twenty paces of where we were first fired at—Mr. Wynn & myself succeeded in catching his horse and stopping him. The firing had now ceased and no one was in sight—save we three—Gen. J. looked up the road towards our troops apparently much surprised at being fired at from that direction, but said nothing. Just then Mr. Wynn saw a man on horseback near by and told him to “ride back & see what troops those are,” pointing in the direction of our troops and he rode off at once—I then remarked, “those certainly must be our troops” and looked at Gen. J. to see what he would say, but he said nothing, though seemed to nodded assent to my remark. He continued looking up the road, standing perfectly still and uttered not a word till Mr. Wynn asked him if he was hurt much, when he replied “severely.” I saw something must be done at once, and as I did not know whether he could ride back into our lines, I asked, “Gen. are you hurt very badly,” he replied, “I fear my arm is broken.” I then asked, “where are you struck,” said he, “about half way between the elbow and shoulder.” I asked, “Gen. are your hurt any where else,” he replied, “yes, a slight wound in the right hand.” I did not think from his looks that he could ride back into our lines for I saw he was growing very weak from loss of blood, nor did I know but what that same Brigade would fire at us again if we approached their line from that directions as we were then directly between our friends and the enemy, and if any difference nearest the enemy, and I was fearful the enemy might come up and demand our surrender as there was nothing to prevent it. I could not tolerate for one moment the idea of his falling into the enemy’s hands. I then asked the question, “Gen. what should I do for

[page 4]

you” when he said, “I wish you would see if my arm is bleeding much.” I immediately dismounted, remarking, “try to work your fingers, if you can move your fingers at all the arm is not broken,” when he tried & commented, “yes it is broken, I can’t work my fingers.” I then caught hold of his wrist and could feel the blood on his sleeve and gauntlet, and saw he was growing weak rapidly. I said, “Gen. I will have to rip your sleeve to get at your wound”—he had on an india rubber overcoat—and he replied “well you had better take me down too,” at the same time leaning his body towards me—and I caught hold of him—he then said “take me off on the other side.” I was then on the side of the broken arm & Mr. Wynn on the other. I replied and started to straighten on his horse to take him off on the other side, when he said “no, go ahead” and fell into my arms prostrated. Mr. Wynn took the right foot out of his stirrup & came around to my side to assist in extricating the left foot while I held him in my arms and we carried him a little ways out of the road to prevent our troops or any one who might come along the road from seeing him, as I considered it necessary to conceal the fact of his being wounded from our own troops, if possible. We laid him down on his back under a little tree with his head resting on my right leg for a pillow, and proceeded to cut open his sleeve with my knife. I sent Mr. Wynn at once for Dr. [Hunter] McGuire & an ambulance as soon as I ripped up the india rubber, I said to him that I would have to cut off most of his sleeve, when he said “that is right, cut away every thing.” I then took off his opera glass & haversack which were in my way—remarking, “that it was most remarkable that any of us had escaped alive” & he said “yes it is providential.” I was then under the impression that all the rest of the party accompanying him had been killed or wounded, which was not far from the truth. Gen. J. then said to me “Capt. I wish you would get me a skilful surgeon.”

[page 5]

I said “I have sent for Dr. McGuire and also an ambulance, as I am anxious to get you away as soon as possible, but as Dr. McGuire may be some distance off, I will get the nearest Surgeon to be found, in case you should need immediate attention,” and seeing Gen. Hill approaching the spot where we were, I continued “there comes Gen. Hill, I will see if he can’t furnish a Surgeon,” and as Gen. H rode up, I said “Gen. H have you a surgeon with you, Gen. J. is wounded”—said Gen. H. “I can get you one” and turned to Capt. B[enjamin] W. Leigh who was acting aid de camp to him and told him to go to Gen. [Dorsey] Pender & bring his surgeon. Gen. H. dismounted and came to where Gen. J. was and said “Gen. I hope you are not badly hurt.” Gen. J. “my arm is broken.” Gen. H. “Do you suffer much.” Gen. J. “it is very painful.” Gen. Hill pulled off his gloves which were full of blood, and supported his elbow and hand, while I tied a handkerchief around the wound. The ball passed through the arm, which was very much swollen, but did not seem to be bleeding at all then, so I said, “Gen. it seems to have ceased bleeding, I will first tie a handkerchief tight around the arm” to which he said, “very good.” I then said, “I will make a sling to support your arm,” to which he replied, “if you please.” About this time the Surgeon of Pender’s Brigade, Dr. [Richard R.] Barr came up and Gen. Hill announced his presence to Gen. J. & Gen. H. offered a tourniquet to fold around the arm but as it was not bleeding at the time and seemed to be doing very well, it was not put on. The Surgeon went off a few minutes for some thing & Gen. J. then asked in a whisper “is that man a skillful surgeon.” Gen. H. said, “he stands high in his Brigade, but he does not propose doing any thing—he is only here in case you should require immediate aid of a surgeon or till Dr. McGuire reaches you” Gen. J. “very good.”

[page 6]

At this time Capt. [Richard H. T.] Adams, signal officer offered Gen. Hill whiskey for Gen. J.—which Gen. H. asked him to drink. He hesitated and I also asked him to drink it, adding that it would help him very much. Gen. J. “had you not better put some water with it”—which was the cause of his hesitation. Gen. H. and I both insisted on his drinking it so and taking water after it, which he did. I then said “Gen. let me pour this water over your wound,” to which he said “yes, if you please, pour it so as to wet the cloth,” which I did & asked “what can I do for your right hand” Gen. J. “don’t mind that it is not a matter of minor consequence—I can use my fingers & it is not very painful.” About this time Lts. Smith & [Joseph G.] Morrison came up and Lt. Smith unbuckled his sword & took it off. About this time Capt. Adams halted two Yankee skirmishers in a few yards of where Gen. J. lay and demanded their surrender. They remarked, “we were not aware that we were in your lines.” Gen. Hill seeing this immediately hurried off to take command, saying to Gen. Jackson that he would conceal the fact of his being wounded. Gen. J. said, ” yes, if you please.” Lt. Morrison then reported that the enemy were in a hundred yards and advancing & said, “let us take the Gen. away as soon as possible.” Some one then proposed that we take him in our arms, which Gen. J. said, “no, if you will help me up, I can walk.” He was immediately raised and started off on foot with Capt. Leigh on his right side and some one, I am not sure who was on the left side to support him. When he walked a few paces he was placed on a litter borne by Capt. Leigh, Jno J. Johnson and two others whose names I am not certain of. Jno. J. Johnson of Co. “H” 22 Va. Battalion was wounded while per-

[page 7]

forming this duty and his arm afterwards amputated at the socket. I could take no part in bearing the litter as I had not sufficient strength in my right arm to assist, in consequence of a wound received in a previous engagement, so I got on my horse and rode between Gen. J. and the troops who were moving down the road, to prevent if possible them seeing him and was leading a horse belonging to one of the litter bearers, which I also endeavored to keep between him & the troops in order to screen him more effectively. These troops seemed very anxious to see who it was that was wounded, they kept trying to see and asking me who it was, and seemed to think it was some Yankee officer as he was being brought from the front of our lines. To all of these questions I simply answered, “it is only a friend of mine.” Gen. J. said “Capt. when asked just say it is a Confederate officer.” One man was so determined to see who it was that he walked around me in spite of all I could do to prevent it & exclaimed in the most pitiful tone, “Great God that is old Gen. Jackson,” when I said to him, “you mistake it is only a Confederate officer—a friend of mine.” He looked at me in doubt & wanted to believe but passed on without saying any more. As soon as Gen. J. was place in the litter the enemy opened a terrific fire of musketry, shell, grape & C. which continued for about half an hour—to all of which Gen. J. was exposed. One of the litter bearers had his arm broken but did not let the litter fall—then another man just after this, fell with the litter, in consequence of getting his foot tangled in a vine. It was entirely accidental & he expressed great regret at it. Gen. J. rolled out & fell on his broken arm, causing it to com-

[page 8]

mence bleeding again and very much bruising his side. He gave several most pitiful groans—but previous to this he made no complaint and gave no evidence of suffering much. After this he asked several times for sprits, which it was very difficult to get. He was much in need of a stimulant at this time as he was losing blood very fast. I went to a Yankee hospital near by and tried to get some sprits for him from their surgeons, but they had none. At this time Dr. McGuire & Maj. Pendleton got up & Dr. McGuire found him in an ambulance very much exhausted from loss of blood & he gave him some sprits—which seemed to revive him somewhat. He was then carried in the ambulance a mile or two to the rear. Just here Maj. P said to me “Capt W., Gen. Hill is slightly wounded in the leg and Gen. Rodes is in command & requests me to send for Gen. Lee & ask him to come here. I wish you would go to Gen. [Robert E.] Lee with this intelligence and send for Gen. [J. E. B.] Stuart. There are a plenty here to take care of Gen. J & you have done all you could do.” I asked Capt. Randolph of the couriers to go for Gen. Stuart and he started for Gen. Stuart. I reached Gen. Lee about an hour before day and found him laying on the ground [a]sleep but as soon as I spoke to Maj. [Walter H.] Taylor, he asked who it was & when told, he told me to come & take a seat by him & give him all the news. After telling of the fight & victory, I told him Gen. J. was wounded—describing the wound—then he said, “thank God it is no worse, God be praised that he is yet alive.” He then asked me some questions about the fight & said “Capt. any victory is dearly bought that deprives us of the services of Jackson even temporarily.” When I returned to Gen J. his arm had been amputated & he was doing well.

Respectfully

R. E. Wilbourn

Capt. & Chief Signal Officer

2nd Army Corps